Learning to understand another’s intent is the most complicated lesson we are trying to teach our son with autism.

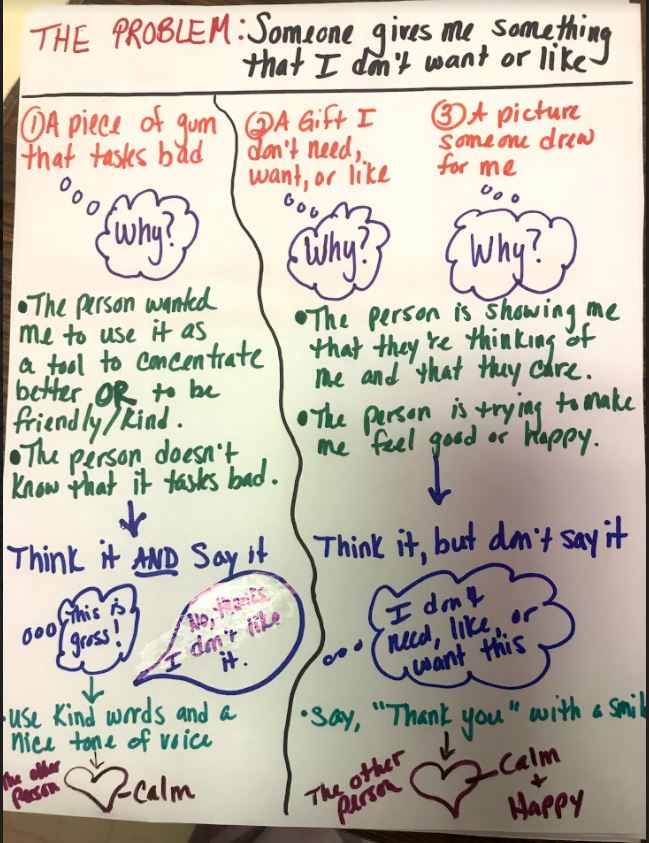

This first started from a program he began working on in school and with his home therapist more than a year ago. We give him a situation and ask him, “Should you think it or say it?” Most parents cringe when their young children say something out loud that is inappropriate, like when my 3-year-old niece called an overweight man “humpty dumpty.” That same situation coming out of a 9-year-old kid can be downright harmful.

So recently, my son told me that at school, his teacher had given him a piece of gum. (He is allowed to chew gum at school for his oral fixation.) He told me with pride, “The gum tasted bitter and I did not like it, but I just thought it and did not say it!” I responded by telling him, “Well, in that situation you could have politely told her, ‘No thanks, I don’t like this flavor.'”

He was, understandably, frustrated and confused. Why is OK to “say it” in some instances but not in others? I had no answer. How do I explain his teacher’s intent?

Well, for starters, his teacher was not giving him the gum as a gift. Let’s say, instead, someone gave my son gum as a Christmas gift because they know he loves to chew gum. So thoughtful! But, uh oh, it is not Extra brand sweet watermelon flavor (the only gum he likes). He should just say, “Thank you.” It would be rude if he said, “I hate this gum.” It would hurt the gift-giver’s feelings.

The gum-at-school situation was the same: Someone gave him gum he did not like. But the intent of the giver was different.

My son’s blunt honesty and lack of filter can be funny to those who know him and love him. Like when he told my sister, “Your family has the worst hot dogs in the world.” We all laughed. But that same trait can make it difficult for him to make friends — and it could, ultimately, affect his adult life in a major way.

So this is an extremely important social skill for him to learn — and it’s equally as difficult to break down and teach. This is a social skill that neurotypical children will pick up on their own. This difficulty is unique to my family (and to other families dealing with autism spectrum disorder). This is why my son is in a sub-separate classroom. This is why he has home therapy six hours a week.

Here is an example of how his speech and language pathologist is breaking this down:

This is a burden we bear that other families may not. This is why our son and our family need acceptance and awareness. Both my son and our family are dealing with some very exhausting, difficult, and complex issues.

I am grateful for all the support from my son’s teacher and therapist. But I also need support from my fellow moms and my community.

If you have an autism family in your life, I encourage you to reach out to them. Ask, “How are you doing? What are your struggles?” Be aware, be understanding, and be accepting that they are exhausted from these very different and often challenging goals.